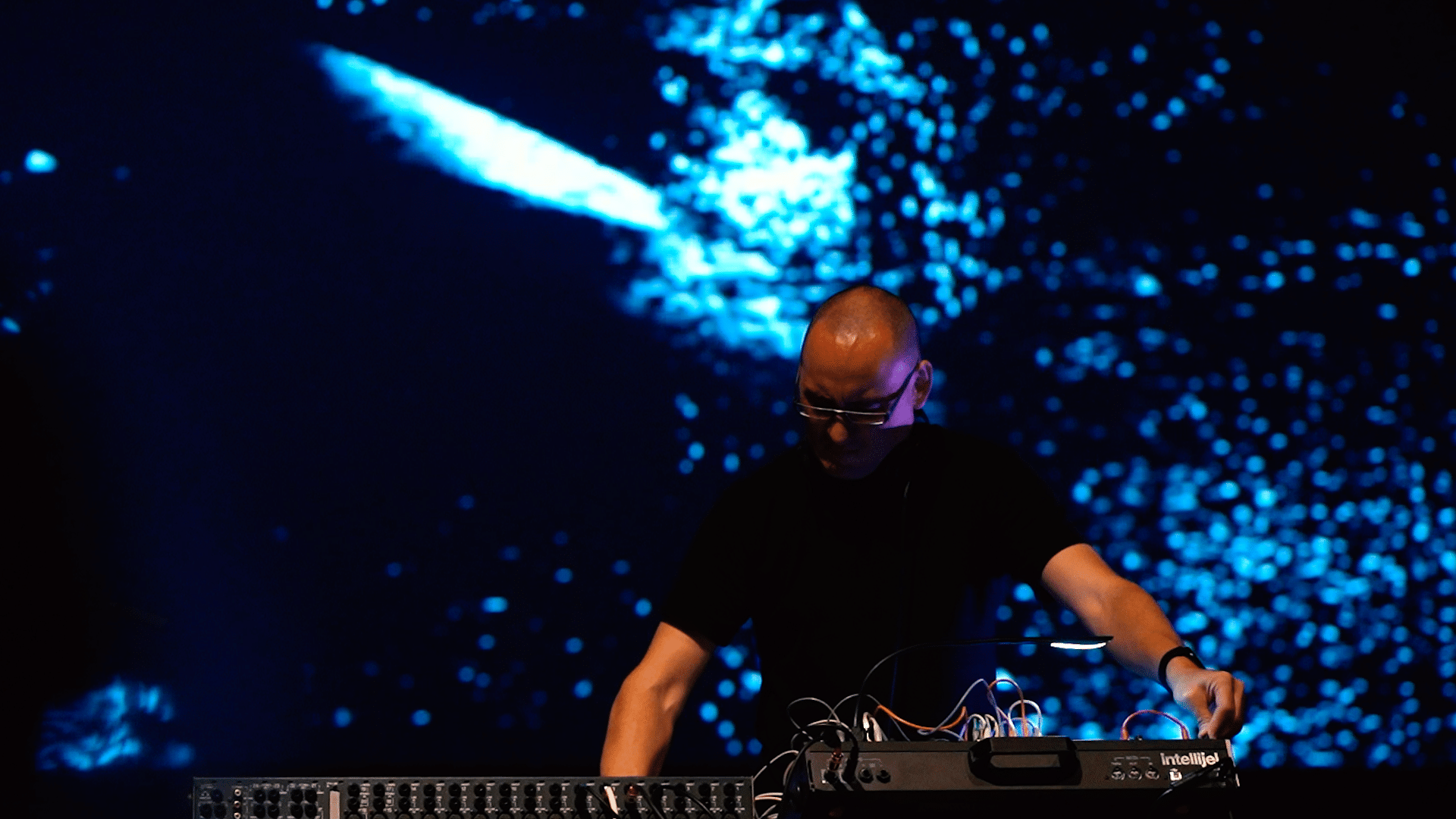

Gamechanger Audio artist

Richard Devine is definitely a deep-sea creature. For the looks of it, this man embodies sunshine and his voice could easily soothe all your troubles away but put him in front of the right gear and a whole new world arises. From techno beats, rave sets and frequencies that scratch the most inner parts of your brain to useful sound design of everyday tools – Richard lives a life where every knock, beep, and screech is a part of a bigger picture. He’s known for his enthusiasm towards gear and companies that can help him shake that picture into cosmic rays, that’s why we had to sit him down and see how that kind of brain developed into what it is. Turns out, it’s not as mysterious as we thought, but it’s definitely a life that sounds a lot different than we could imagine.

Richard: Initially, I think, it was all by accident. It was my mom. It was her fault. She got me and my brother involved with piano lessons probably around the age of 7 or 8. It was a classical piano. At that age, it was not something we were interested in doing. We wanted to play in the creek and catch poisonous snakes, ride BMX bikes and skateboard, you know. Learning piano or having anything to do with music at that time was the farthest thing that we wanted to do.

I think it was my last piano teacher who asked me a profound question: “You’ve been playing piano, playing these pieces of music, does it bring you any enjoyment or is your mom just making you do this?” I said: “Yeah, my mom’s just making me do this!” To which he answered that this isn’t the reason you should be playing music. I sat there and I was honestly perplexed by that sentence when he says you should be playing because you enjoy this. “Is there any music you enjoy?” he asked me. I hadn’t really heard anything, I’d just had to sight-read music – it’s almost like reading a book. At that time it was more like “CAN I read this book?” – get the timing and proper playing etiquette and play through these recitals. I was missing the point, the emotional aspect of music. That teacher taught me that you should be playing music cause it emotionally provokes you a certain way. And, so, he’s approach was just to play lots of different music from different composers. He played me music from Erik Satie, Haydn, Schmidt, and Beethoven the full … from different composers and different time periods. And I started to gravitate towards certain things like, I started to actually find things that I liked. That was the beginning, that was the spark.

But I was also very young and influenced by the skateboard culture – me and my brother were skateboarders. Along with skateboard culture came the music, and during that time we were listening to a lot of DIY punk music, everything from Dead Kennedys to Minor Threat, Misfits, D. R. I. (Dirty Rotten Imbeciles) – those types of bands. Then there was also a lot of hip-hop cause a lot of my skateboarder friends would listen to early EPMD, Public Enemy was a big one for us, Eric B. & Rakim… the late 80s, early 90s hip-hop stuff. It was a big part of my upbringing. And then when industrial music emerged it was like taking both of those worlds coming together – the synthetic sounds of hip hop with the raw edginess of punk music and making this new thing that was happening. That really, really sparked my attention.

M: So it was the whole community and the culture surrounding that music. And your piano teacher was the one who taught you to listen, to actually understand the purpose of music and to think about what you like.

R: Exactly! All my teachers prior to that were just teaching a technique. Teaching to read and to play properly. But none of them were really getting to what the root of the most important thing is – the emotional connection to music. What are you emotionally feeling from the music? I’ll never forget that, it was never the same after that when I learned that it’s not about playing the music perfectly or reading a piece of music perfectly. It’s about emotionally conveying something – an idea, or communicating an emotion to people that they can feel cause music is just another tool to communicate or express an emotion to people. And it could be extremely provocative and thought-provoking to me.

That’s when I started to seek out more music that could push my mind in different ways – whether it was punk or industrial, or noise, or classical, or jazz, it didn’t matter. I began becoming a music addict at that time. I would say shortly after that, I mentioned to you guys, that I tried to start a few bands in high school which came out unsuccessful. I couldn’t get friends together to form a band. So eventually I bought a drum machine and just said “I’ll do it on my own”. Just start figuring it out. And right around that time the rave movement hit in early, mid 90s in Atlanta.

M: Do you remember the exact drum machine?

R: Yeah, I think the first drum machine I had was an HR-16 BIT . It’s a grey, really crappy, old drum machine, but it taught me the basics of programming and arranging songs. Then from there, I got a TR- 909 drum machine. A friend that used to work at a graphic studio in Atlanta was unloading it and I think I bought it for like 400 bucks, I mean, it was nothing. I know they go for a lot of money now. I learned a lot on that drum machine – the Roland. I guess the Roland 909 was where I started sequencing and arranging songs, plus a lot of the music I was listening to at the time was using the TR-909 drum machine as a bass, as a lot of the groundwork for the rhythm. So it was the perfect first machine to learn on. That for me was the early beginnings. And from that point, I mentioned the rave movement, I started to go to a lot of parties and was influenced by a lot of the sort of midwest sound, sounds of Detroit, techno, electro, people like Quantec, Model 500 and Drexcya – they were really big influences on me.

M: Everything that happened in Chicago and Detroit.

R: When I was growing up in high-school I would go to this record shop in Atlanta called “Let The Music Play” and I would actually go in the reject bin – they had a bin of all the records that the DJs wouldn’t play because they wouldn’t fit the most popular current styles. I would go every Friday and I would buy all the stuff that they didn’t… they were way too dangerous to play on a dance floor, it was too weird or it was ordered by accident. I found so many great records in that bin that were some of the strangest music that I had ever heard. It really opened up my mind to a whole new world of electronic music that wasn’t necessarily just designed to be played in a club. Some of this music was just – “Hey, take a bunch of drugs and see where it takes you!”

I continued to seek out more music in that direction. That began my journey into more experimental music – I found composers in the academic realm, electroacoustic composers, people doing experimental noise, field recordings. It went all over the place. And I discovered that sound wasn’t just a band or a person playing one instrument – it could be someone recording EVP recordings of dead people – who knows! I mean, it could be whatever your perception of what music is… I think when I bought John Cage’s “Variations” record, he completely flipped my whole view on what music could be. I remember studying Stockhausen’s “Kontakte” record, I remember getting that record from a friend of mine and tripping on acid just being completely perplexed listening on my parents’ record player to it over and over, thinking how demented is this person. It made me question everything about music, what music even is. The structure of music, does it even have to have the melody, does there even need to be rhythm. I love that. I loved any kind of music or artist that made me question any of those ideas of what even could be a music composition. Cause sometimes I would play these records and my mom would come in and say “What is this!? This sounds like just a bunch of metal pans hitting each other!” I thought: “Yeah, maybe to you. But I hear other things in this that you’re not hearing.”

M: Do you think that this ability to actually see the other side of what music and what sound can be is the ability that allows you to work in sound design as a professional?

R: Actually, I didn’t realise it at the time, but I was cataloging and recording a lot of sounds back in the late 90s. I was using portable DAT recorders which was digital audiotape. And then eventually I moved over to MiniDisc recorders which were these portable kind of mini CDs. You guys probably… I don’t know, for the newer generation, you probably have no idea what those mediums were. But I used to record with these little stereo T microphones. I would record insects, ambiances, machinery, and I would catalogue these sounds. Then I would put them in my sampler and use them in music compositions. I didn’t realise the term back then “sound designer” – that wasn’t even a term back in the early 90s, mid-90s when I was capturing all these sounds and using them in my compositions. It was just… a collage of found sounds that I was able to use as extra elements. And I didn’t realise I was training my ears to listen for things – “Oh, that sound, if I could take that sound and pitch it down an octave or two octaves, make this sound larger than life and turn it into something completely different”. Your ears start clinging on to things and you’re able to… it’s almost like they’re pieces of lego or a puzzle. You start to think: “This one would be perfect for here, this piece will be great for this part in the composition and this will make a great transition point”. You start thinking about sound completely differently, sounds that people don’t even pay attention to that happen every day in the outside world. I started to pay attention a lot more and I didn’t realise that all of those skills would later play a huge part in me working as a sound designer – using those types of sounds and applying them to film and video games, and various other media which required that exact skill of taking found or folly sounds and then incorporating them into a TV commercial. I worked with many advertising agencies where I was scoring to picture just sound design, you know, like, a car commercial where I had to record a whole car or some product where we had to go out and capture stuff out in a field. It was the same idea, you’re just taking it and telling a story – you’re telling a story with sounds scored to a picture. It was an interesting skillset to build up. But like I said – it all happened by accident.

M: Yeah, you mentioned that this term sound design didn’t even exist.

R: It didn’t!

M: How did you manage to turn this into your profession?

R: That also happened by accident. I was approached by a company Native Instruments from Berlin, Germany. They make software that a lot of people are familiar with and hardware. They approached me in 1999 or 98 about working on some sample libraries for them and programming cause one of the guys who worked at NI, at artist relations, was like: “Hey, we love what you did on this record. We’re really into your sound, we would love to work with you!” I had never worked with a company before other than just making sounds for my own productions. At the time they were a very small company, they were only 6 people. I remember visiting their office in Berlin and thinking “Oh, these guys are cool, they’re making this interesting software called Generator” Kind of like this underground… at the time they were this underground software company making really innovative, interesting tools that were for people like me who wanted to manipulate sound in ways that I’d never been able to do before, so, obviously, I agreed. And that began this long relationship – I’ve continued working with them even till today, I’m still working with them since the beginning. That decision eventually snowballed because other companies heard my work. It was the first computer wave when people started making a lot of music in the computers – the software revelation happened, VST instruments happened and NI released their, I think it was the Hammond B3 and the Pro 53, which were the two most realistic kind of emulations of the real hardware instruments. That took everyone by storm. It was kind of the first time when everyone realised “Oh, wow, a computer actually can be a very sophisticated instrument.” and started to really take it seriously at that point. That kind of kickstarted things and other companies started getting involved. I started working with NI on their sample library department, with Kontakt and Battery. Then they started divisioning out to synthesizers like Absynth, FM7, Massive, so I was asked to work on and design sounds for some of these synthesis platforms. That really was just the beginning of it. I had no idea that their software was gonna end up in these commercial studios all over the world, film studios, gaming studios, commercial houses, you name it. People were buying their software and, of course, every time you opened one of their applications, the first thing that comes up is all the programmers that created the software and then the sound designers who created the presets – we were always listed in the credits. I was getting calls all the time: “Hey, we heard your presets that you did for Absynth or this. We’d love to work with you!” Before you know it companies like Clavia Nord and Korg, and Roland and a lot of the major keyboard manufacturing companies started to jump on and were asking me to work doing sounds for them.

M: And now you’re working side by side with all these companies.

R: Yeah, it came a full circle. I never… if you would’ve told me 15 years down the road that I’d actually be making sounds for the companies that I first started to use gear from, I would’ve laughed. It would’ve been a really funny idea, I never would’ve dreamed that I’d be doing what I’m doing now. The stuff I’m doing now, I couldn’t have never even in my farthest dreams had imagined that that’s what my job would be today. Even when I was in college, I always thought I was just gonna get a normal job and do music as a hobby. But that never happened. My music career just kept staying in the fast lane and never let me out of the it. So, I just said: “Hey, I guess I just have to keep driving this car and see where it goes!” It’s been a really fun journey since that point.

M: You’ve spent a lot of time now working with these big companies. You told us that you have a really good eye for new companies – for new small companies who are just pushing their way out. What was the spark with us – how did you end up seeing us, what struck you to pay attention to a company like Gamechanger Audio?

R: I’m always searching out new companies that are pushing things or trying something different whether that’s an instrument or processing effect, or a piece of software, doesn’t matter what format it is but if they’re trying to do something that’s new, that hasn’t been done before, that’s unique, that brings something new to the table – that always catches my attention or my ear. And I’m always constantly looking for any kind of tools that can bring me very, very unique results very quickly. Funnily enough, I found out about the Gamechanger Audio stuff through a friend of mine – my friend Brian who is also a well-known composer, sound designer. He pulled me aside at NAMM and said “You gotta come to check this. Your mind’s gonna get blown away. You’ve never heard anything like this.” I always trust Brian’s opinion cause he’s always looking for new things as well, he’s like me – constantly searching for the next cool thing. And I remember him bringing me over to the Gamechanger Audio booth at NAMM where I got a demo of the PLUS Pedal. It’s almost like the spectral FFT sustaining pedal, I had never heard anything like it. I’m a huge fan of FFT spectral freezing but I was always doing it in the computer and it was never a thing that was… to do it in real-time, it was always very CPU intensive. And the results were always kinda iffy – it was okay sometimes and sometimes not, but then I heard that pedal. It really blew my mind away, I was like “Wow, these guys are on to something!” Being able to freeze a layer, then add another layer on top of that, and impose another layer… I was just amazed! First of all the quality of the sound blew me away and then – how easy it was to do something that was for me in the past an extremely complex thing to do in the DSP realm. Now it was just one sustain hold away in a really nice form factor with the pedal. And then that’s what eventually led me to look at some of the other products you guys had – going from there, from the PLASMA – pedal and module, collaboration with the Erica Synths. I’m also a big fan of the Erica Synths modules. Once I knew that you guys were collaborating with them I knew you gotta be cool. Cause I love all the Erica Synths stuff and it just, it grew from there. And I’ve been a big fan of all of the products that Gamechanger Audio has been making – you guys are thinking outside the box. You’re not just trying to reinvent something that’s already been done. A lot of pedal and instrument companies are trying to follow the current craze “Oh, everyone liked this instrument 20 years ago, let’s do the new version of that!” You guys aren’t doing that, you are trying to do really unique and new things which I really respect. I really respect companies that take a gamble, throw the dice and say “Hey, you know what, we’re not gonna reinvent the wheel. We’re gonna design a whole completely new concept and see what happens.” Yeah, it’s gonna be risky but taking that risk will yield interesting results, and for people like me – help us create sounds that have never been heard before.

M: It’s the same approach that you do with your music. Not going the safe path.

R: Exactly. And I gravitate towards companies that have that same sort of idea. Where they don’t wanna go with the… at least that seems to me from my perspective as seeing you guys as a collective that is really trying to do some new things that haven’t been done before and doing them in a very unique way – where everything is perfect, where aesthetics are really nice, and then the auditory fact that is really interesting as well. It’s hard to find a company where all of those elements are just… it’s the perfect mixture of all that together that creates this really unique thing that inspires you to want to do stuff with it. That’s hard to find. So that’s what really drew me to you – that creative spark “Hey, this is really cool stuff, I wanna do something with this.” That’s really where it began with me and you guys.

M: What should we build next?

R: You know what? I’m really getting into machine learning. That’s been my new area… I was discovering the work of David Cope, I don’t know if you guys know – he was a teacher, composer, wrote a lot of books on AI-generated music, machine learning generated music – stuff that he wrote like 20 years ago. And now with all the new technology that’s out, I’m really fascinated by this idea of procedurally generated synthesis and algorithm, using algorithms to learn music that you like or playing styles, like what if you had an algorithm that could… say you like Steve Vai or some artist, it could take every Steve Vai song, analyze it and generate hundreds of different mutated versions of Steve Vai songs in a second. And then you just pick the one you want. Or maybe you pick pieces and sections of that song and then you could take that data and you could repurpose it and create some new music. Or maybe you confuse the algorithm and you feed it 15 different pieces of music that have nothing to do with each other and see what it computes. I feel like abusing that technology would be interesting just to see what – maybe we could create some strange, just completely obscure, a bizarre form of music that’s never been heard of before.

+1 202 657 4587

Gamechanger Audio

Tomsona str 33A

Riga, LV-1013

Latvia